On the Verge of Madness

August 16- 2021

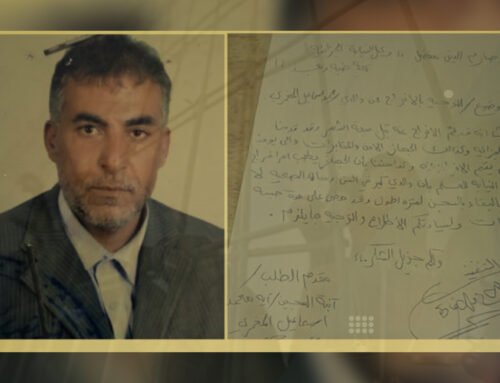

Wael Walid (pseudonym) is a 31-year old man who was one of the young pioneers who responded to the call of the youth revolution for change when it was launched in the square of Sana’a University in the beginning of 2011.

He participated in a sit-in in a pitched tent on Sixty Street, hoping that he and his colleagues, who had graduated some years ago, would be able to get jobs. After the concluding political agreement establishing the Transitional Authority, he returned to his hometown with a spark of enthusiasm to continue working to achieve the goals of the revolution.

On September 21, 2014, the Ansar Allah (Houthi) armed group and the supporters of former President Saleh stormed the capital, Sana’a, and took control of state institutions, military camps, ministries, and public bodies. Then continued expanding their territory to try to control the rest of the governorates of the country.

By that time, Wael had married the girl of his dreams and they had a young son who was a little over a year old. He was eager to settle comfortably in a stable livelihood to support his wife, son, and parents, who all live together in the same family house.

Therefore, he opted to focus on working with his father, staying away from any media or political activity, including posting on his Facebook and Twitter accounts. Although Ansar Allah had taken control of his city in 2014, he hoped that they would stop pursuing him.

Although he suspended his public activism after the intervention of the Saudi-led coalition in March 2015, Wael, along with other non-Houthi young activists who participated in the revolution, found themselves targeted and prosecuted by Ansar Allah, especially those affiliated with the Yemeni Congregation for Reform (Islah) Party.

Starting in 2018, Wael was detained in several places and subjected to various forms of violence, including both physical and psychological torture. As one of the lucky few disappeared persons to return back, he recounted the anguish of the time he spent disappeared:

Charges First, then Interrogation

“On September 9, 2018, I was in my shop, as I used to go every day. I was surprised to see two Houthi gunmen whom I knew well enter my shop in civilian clothes to my shop and ask that I go with them to the Criminal Investigation Department.

I closed my shop and went with them. I assumed that they would take me to the Criminal Investigation Department, detain me for two or three days, and then release me. This had happened previously several times on accusations of suspicious posts on social media and other websites.

But that day, I was summoned in the middle of the night from the detention cell to an interrogation chamber where several interrogators and photographers were present. There was a wooden plate with my name written as well as the number of the case, the political charge, the date, and the day. They ordered me to hold it so that I could be photographed from the front, the sides, and back.

When I asked them how they could photograph and charge me without investigating me, they replied: “These are orders. Comply with the orders without question.”

After that, they interrogated me for about four hours nonstop without giving me any clear accusation for which I deserved to be arrested, only intimidation. I was subsequently transferred to another cell on the third day.”

Central Prison

“At about ten in the morning, a number of armed men came to my cell. They took me and put me in a security patrol car that was parked in front of the Criminal Investigation Department and took me to the Central Prison in the governorate.

They put me in the political prisoners ward, where I was held with other inmates, some of whom I knew were detained for fabricated charges. Most of them were affiliated to political parties like me. Three days after I was brought to the central prison, I was taken to the interrogation chamber. They handcuffed me with iron shackles and tied blindfolds over my eyes.

I had heard from my comrades detained in the same ward about the violence and cruelty of the interrogation officer, and that he was a very cruel person with no mercy in his heart.

At first, they searched me thoroughly, then took me into the middle of a hall and threw me on the floor in a large room with my arms tied behind my back, in a humiliating manner. I could hear people talking and laughing sarcastically as they chewed qat and smoked shisha, the water of which I could hear bubbling.

About an hour after laying like this, the interrogation officer started speaking to me in a threatening and intimidating tone. He said that he knew everything about me, about my activities, and even the air I breathed. He then asked me if I felt any fatigue. I told him that I suffer from pain in my back, knees, and chest.

He started hitting me with a stick on these spots. Then they made me stand and started asking me questions while I was tied and blindfolded. At the same time, someone behind me was hitting me with a stick. They accused me of very serious charges, of which I had no knowledge. They flogged me severely, all the while asking me to quickly keep switching between standing and sitting.

Whenever I got tired and stopped, they would beat me severely all over my body for several hours before bringing me back to the cell, exhausted. Two days later, they came to my cell at night and took me to the interrogation chamber to repeat what they had done: tying me up, interrogating me, and beating me, but this time the torture was more severe than before. They used different types of sticks and wires, and then they tortured me with electricity until I fainted.

After more than two hours of unbearable torture, I was close to fainting when they threw me on the ground and left. From then on they would come to me every second or third day to tie me up in that room, interrogate and torture me using different types of tools and devices like sticks, wires, beatings with fists, kicks with legs, and electricity. I am not able to recollect how many times it happened.

They asked me about my links and connections with some human rights and media activists in the province and accused me of communicating with the leading figures in the internationally recognized government in Ma’rib province who write against Ansar Allah on Facebook.

At the start, I always replied in the negative and swore solemn oaths that I did not have any contact or communication with them. But they would beat me so badly whenever I denied, so eventually I asked them to write confessions of whatever they wanted, and I would sign them.”

Extreme torture

“They did not bring any official charges against me, other than the charges of posting against them under pseudonyms on social media and websites. They claimed that I was some unknown person who is writing against them online.

Even without a real charge, they deliberately tortured and humiliated me. In fact, they often did not have any questions to ask me, so they would force me to stand naked while they poured cold water on my body and ask me to tell them the story of my life. I would tell them anything that came to my mind. Sometimes they did not like what I said, so they would beat me. It continued in cycles. They accused me of receiving sums of money from the recognized government in Ma’rib, and that I was receiving instructions from Ma’rib to monitor Ansar Allah group. I denied it.

Sometimes, during my interrogation, I would realize that there was an extra person there. I did not recognize him because I was blindfolded, but he would correct some of my information on his own, as if he knew many details about me. He would sit in a corner of the room with his mouth apparently stuffed with qat, egging on the torturer by saying “knock him up” whenever I said something that he did not like. Then I would be slapped on the face once or more times, punched on the head, or beaten with sticks. They beat me and took turns torturing me almost daily.

Beyond beating me with sticks and punching and kicking me, they tortured me with electricity. They would bring electrical cables, attach them to my hips and limbs during the interrogation, and then tell me to say whatever they wanted. I would beg them, ‘Write whatever you want, and I will sign any confession. Save me from this torment.’”

Horror Visit

“Throughout my time there, I was prevented from meeting or contacting anyone. My mother and my wife visited me only once: 63 days after my arrest, my family managed to obtain orders from the Houthi interior minister to allow them to visit me.

This was allowed reluctantly. My mother and my wife came at the appointed time and after their arrival they took me to the prison yard, with masked soldiers escorting me and lining the sides and rooftops above the yard.

Their presence in this manner terrified my mother and my wife, especially because some of them were standing on alert with their guns loaded. The soldiers escorting me were pushing me in front of them and shouting, ‘move, faster, yallah!’

My mother and my wife were crying out of fear, and my mother told me that the guards at the prison gate told her that I was with ISIS they would tear me down and cut me to pieces. Then we were suddenly interrupted by some masked soldiers who spread out around us to take me back inside.

This made my family even more afraid, and their weeping increased. Thus, the visit ended in less than four minutes, after which I cried in pain. It was such a dark day for my mother and my wife, I hoped that they did not allow them to visit me again. While they forced me back to my ward, my mother cried and begged them to let me stay with them for a little longer.

Denying my Presence

After some time, my family managed to obtain an order from the Minister of Interior to release me through intermediaries from our relatives. When the Houthi-appointed security director and prison superintendents learned of this, they quickly hid me in an unknown cell inside the prison. When my family presented the release order to them, they replied that I was no longer with them in the prison, and that I was transferred to the city of Dhamar.

While I was hidden inside the prison, my relatives went to look for me in Dhamar. They went from one superintendent to another, until they got desperate and frustrated, and gave up hope of finding me alive.

The cell where I was hidden with two other inmates was particularly bad: there was no toilet, so we could not clean up or take a shower. We used to relieve ourselves in a sewer in an open area. They brought us very little water.”

An Unknown Basement

“A week after I was taken to that unknown cell, we were surprised when one night they came to the cell. They took me and the other two inmates to the prison yard. Then came a security squad of about nine masked gunmen along with a driver.

The gunmen asked, ‘Where are they? The ones you told us about?’ They pointed to us. We were ordered to get into the truck. Several gunmen were positioned around us on the back panel, while three others sat in the front cab.

They drove us at a crazy speed. We were shivering from the cold as we grabbed the sides of the truck as hard as we could, so as not to fall, drop or be hurled away on sharp turns of the road. We finally reached the Madhbah neighbourhood of Sana’a.

Then they put blindfolds over our eyes and cuffed us with iron shackles to hand us over to another squad of armed men. These men took us to the Al-Saba’een district, where we walked about a quarter of an hour to another neighbourhood, likely Haddah. There they took us to a villa which served as one of the unofficial prisons and locked us in the basement.

My detention and my disappearance lasted exactly 10 months. We did not know where we were being held. None of our relatives knew where we were. All we knew was that the jailers called it ‘Bush Prison.’

Members of my family were also subjected to intimidation and provocation after my enforced disappearance. Anyone who tried to search for me or demanded my release was subjected to this treatment.”

Back to Torture

“Several days after they locked me up in this unknown basement, they interrogated me. The interrogator had a small stick that he would use to hit my elbows and the heels of my feet until I felt numb. Then, he threatened me to electrocute me.

This torture, for me, was less severe than what I suffered in the central prison. There were prisoners who have been forcibly disappeared for three or four years, who told me stories of various forms of torture such as being given very little food to induce starvation.

Here too, they exposed us to extreme hunger. They did not provide us with the medicine that we asked for when we became ill. When we felt symptoms, we would give them money to buy us medicine, usually pain killers. They took the money and did not return. Three or four days later they would come back with the medicine they bought.

After a while, they brought us preachers, or so-called ‘cultural superintendents,’ to give us lectures about the virtues of the Ahl al Bayt [people of the household of Prophet Mohammad] the merit of Wilaya [the event at which the Prophet is said to have announced Ali as his successor], and the achievements of the Qur’anic march. We were forced to sit down and listen until the end.

During our last detention in that basement our psychological and physical health condition deteriorated. We were more than 80 detainees stuffed in the basement with poor ventilation. Not allowed to go out to the open places, we spent about six months festering in the darkness until they started allowing us to go out to the courtyard for half an hour once every ten days, while we were bound.”

Political Opponents as Military Objectives

“Ten months later, I was transferred with some detainees to a camp that was a military target of the coalition. It had previously been under constant bombardment, so I guessed that Ansar Allah used this camp as a prison for their opponents deliberately to endanger us.

At the camp, I found hundreds of detainees and disappeared, including Salafi and other military detainees from what is known as the ‘Al-Fateh Incident.’ The detainees were distributed among large wards that were originally intended for the soldiers’ accommodation. More than 400 prisoners were allocated to each ward.

It was very cold, and windows were broken because the coalition aircrafts had bombed this camp many times before. The bathrooms were crowded. The jailers were masters at torturing us, both psychologically and physically.

For example, during the freezing cold, they would take us out into the yard and force us to take off all our clothes except for our under-garments. They would then spray us with cold water and keep us exposed out in the open while they brought out another group to strip and flog until they were bleeding.

They deliberately terrorized us and put us in a state of constant anxiety, telling us that so-and-so will be released, raising an atmosphere of optimism, until we discovered that it was a trick, and no one was going to be released.

I stayed for nearly two months in this camp in the most frightening conditions. It was especially terrifying when we heard war aircrafts or the explosions nearby. We could not sleep from the intense terror, waiting for when we will die. We were filled with despair and completely lost hope of being released alive.”

Release!

“Two months before the end of 2019, a miracle happened. I learned that I would be released with some other people as part of a prisoner exchange deal between Ansar Allah and the recognized government and the Islah party in Ma’rib governorate.

I was skeptical at first, but this time it was certain, as I indeed was released with some other detainees. I could not believe that one day I would go out, and this nightmare would end. I had been sure that I would die in detention, without ever seeing my mother, wife, and son again.

I was on the verge of madness, especially knowing that I was being unjustly detained. When they gave me a choice between staying in house arrest under their control and being exiled to another governate, I chose to relocate to Marib province with my family, away from my relatives, and my home.”