“How The War Lengthened Our Journeys”

By: Suleiman Al-Nahari

June 27,2021

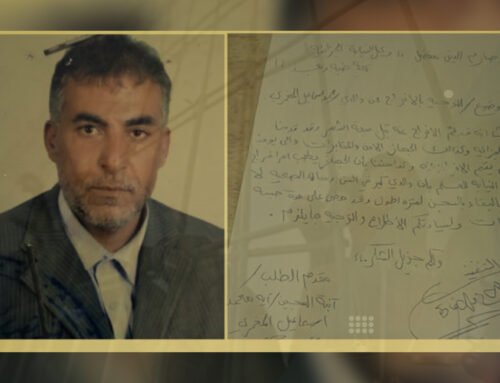

For the plights of traveling in Yemen there are endless stories. Haj Muhammad, of the50 years of age, was neither the first nor will he be the last to taste the harshest of the hardships of Yemeni roads disconnected by warring parties.

Haj Mohammed told us how he got stuck on Friday, 4th of September, 2020, on the frontiers of Ma’rib, beyond “Bab Al- Falaj” checkpoint, that was controlled by forces affiliated to the internationally recognized government. How did they stop him, not allowing him to continue his journey to Sana’a. He has been travelling from Hadhramaut where he visited his nephew, who was working there, to reassure himself on his well-being.

At first, the soldiers in charge of the checkpoint did not disclose to him the reason for stopping him. Subsequently he heard from one of the passengers that there were clashes between government forces and Ansarallah (Houthi) armed group, and that the road was not safe for travelers and was in fact closed to everyone.

Hajj Muhammad waited for two days, Friday and Saturday, in the hope that the road might open to travelers, so that he could continue his way to Sana’a by the bus. He had paid the fare of 15,000 Yemeni Rials, equivalent to 25/16 US Dollars, as a passenger from Hadhramaut to Sana’a.

Hajj Muhammad was lost because he only had a small amount of money left, hardly enough to sustain him for a few more days. By the rise of Sunday morning sun, his situation was getting very dire. His money was about to run out. So, he decided to ride the Hilux truck that was heading from Ma’rib to Sana’a, for a fare of another 15,000 Rials. I was with him in this same vehicle and we had received a promise from the driver that he would take us to Sana’a via a sandy desert road that passes through Al-Jawf Province, which borders both Ma’rib and Sana’a.

The road was a real graveyard of cars in every sense of the word. The horizon was filled with large expanses of sand. Yellow was the colour of the burning scene. The sun was not more merciful than the war itself; we were almost roasting in the scorching heat.

We set off, and were going at high speed; because slow speeds would cause the car to get bogged down and stuck in loose sand, and we would not be able to continue our journey.

Halfway through the distance, we saw a horrific and terrible spectacle that we, the travelers, will never forget. Cars, buses, trailers, trucks, as well as small cars, were all stuck in the sand as if they were victim corpses scattered round the place.

We were riding, holding our hearts with our hands scared of being stuck next to them. There were no communication networks, no internet, and no sign whatsoever of our whereabouts in that grim desert. We could only hope for some sympathy in the heart of some traveler who passes by us, that his sense of desert chivalry may prompt him to help us, to survive together or sink together in this sea of shifting sand.

We took pity on one of the Hilux vehicles whose driver had set off with us after we saw him fall into the sinking sand trap in front of us. We couldn’t turn our backs on him. Our Hilux driver stopped to help after he drove to park on a relatively safe ground area away from sand.

We could not get the Hilux unstuck out of the sand. The desert was more traitorous than we anticipated. We were 21 passengers from both cars trying with all our strength to extract the car out of the deep sand or lift it away from the danger zone.

We were pulling it some 40 centimeters only to get it back into the same trap. We tried over and over again, and before every attempt we excavated the sand under the wheels of the car, hoping this digging would reduce the car’s contact with the sand. After we got exhausted by fatigue, we turned around and there was a “Vitara” car stuck near us. Its driver called us for help, so we went to help him. When we asked him how long has he been stuck? He replied in an angry and frustrated voice: “Since yesterday morning I have been stuck here without water.”

We fetched some water for him from what we had and we gathered our strength and determination to help him, but his luck was no better. We tried with all our strength, but his worn out car did not respond. We let him to complain to his Lord the desperation of his situation, and left him without being able to help.

We went back to the other car, that was traveling with us, to have another go. Digging under the four wheels of the car, we hoped the predicament would be eased. On one occasion, Hajj Muhammad was digging in the sand with us, as his phone dropped from his pocket without anyone noticing or seeing it. He continued to dig, moving from one wheel to another until relief came 45 minutes later, during which we were able, after so much efforts, to save the car from the desert.

We continued to travel for about eight hours until we reached Sana’a. Everyone was happy to arrive safely although our skins had changed under the burning sun rays. Our faces were dusty and our heads looked like they have been pasted in soil. I was in no better shape than others though I was inside the car with four others while the rest were on the roof.

Then it was time for payment. We had agreed with the driver that the passenger fare would be 15,000 Yemeni Rials. He collected the fares from everyone, and when it was Hajj Muhammad’s turn, the car owner raised the pitch of his voice and started shouting that he would not accept the fare that was offered by Hajj Muhammad.

I approached to find out more. The driver was scolding Hajj Muhammad and asking him to pay his fare with old currency and not with new one. Hajj Muhammad was trying to explain to him that he joined the trip in Ma’rib, where these prints of new currency are in circulation.

“You are now in Sana’a,” replied the driver, “and you have only paid me in Sana’a. I will not accept this currency from you, and if you insist on paying me with it, I will add 25% as exchange rate difference, meaning you have to pay me 20 thousand Rials.”

Hajj Muhammad was surprised by the man’s attitude and told him that his money would not be enough for him to contact his family after he had lost his phone while helping to get the car out of the sand.

It was a scene devoid of humanity and kindness. Hajj Muhammad, who symbolized the helpless citizen, had no choice but to pay to the driver, who suddenly became aggressive, uncompromising and caring for nothing but to have his payment without any deficit.

After more arguing, Hajj Muhammad gave in, and paid the extra 5,000 Rials to the driver. He made one last simple request to the driver. He asked him for 500 Rials (less than a dollar) in old currency, in order to reach one of his relatives . In a moment when I was distracted by the situation, Hajj Muhammad had disappeared from my sight.

This is the war. It has surged its tyranny on the people and left them weak in the face of its brutality. Every facet of the lives of Yemenis, including travel within their own country, has become a piece of hell